Executive Summary: Strategic Quick Reference

As global manufacturing shifts from the “why” of 3D printing to the “how” of industrial integration, selecting the correct laser engine determines the viability of the entire production line. This guide analyzes the five dominant laser technologies through the lens of performance, cost, and strategic ROI.

| Laser-Typ | Primary Application | Key Advantage | Strategic Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faser | Metal SLM | Highest relative density; mature ecosystem. | High thermal stress; complex post-processing. |

| CO₂ | Polymer SLS | Support-free geometries; material versatility. | Lower precision/surface finish than UV. |

| UV | Resin SLA | Superior resolution and surface finish. | Limited material strength and heat resistance. |

| Nd:YAG | Metal Cladding/AM | Specific metal absorption; solid-state stability. | Lower efficiency than modern Fiber systems. |

| Diode/Pulsed IR | Area Printing | Massive scale; decoupled cost/productivity. | Fixed 25 µm layer thickness; emerging tech. |

1. Introduction: The Strategic Role of Lasers in Modern Industry

In the current “Industry 4.0” landscape, laser technology has matured from a specialized laboratory instrument into the essential bedrock of high-precision manufacturing. Lasers are no longer just cutting tools; they are high-energy architects capable of generating complex geometries that traditional casting or forging cannot replicate.

This guide leverages deep expertise in material science and photonics to demystify the five core laser types: Fiber, CO₂, UV, Nd:YAG, and Diode/Pulsed IR. While other energy sources like Electron Beam Melting (EBM) represent a mainstream process for high-thermal, brittle materials in vacuum environments, laser-based systems remain the dominant force in the global AM market due to their versatility and atmospheric flexibility.

2. Fiber Lasers: The High-Precision Metal Specialist

Fiber lasers currently hold strategic dominance in the metal additive manufacturing (AM) sector, primarily as the engine for Selective Laser Melting (SLM). Their market position is bolstered by significant software and mechanical maturity, making them the “gold standard” for critical aerospace and medical hardware.

Generation Principle

CORRECTION: Fiber lasers operate at wavelengths of approximately 1.06-1.07 µm (commonly 1040 nm or 1064 nm), not 1.09 µm as sometimes cited. Modern fiber lasers used in AM are typically ytterbium-doped (Yb) fiber lasers pumped by diode lasers at 950-980 nm. These systems are prized for high electro-optical conversion efficiency (approximately 25%) and a beam mode that closely matches the fundamental mode (TEM00). In an SLM configuration, the laser is directed through a sophisticated optical chain—including beam expanders and F-θ focusing lenses—to precisely melt metal powder beds.

The “So What?” Layer: Strategic Value

The 1.06-1.07 µm wavelength is specifically optimized for high absorption in industrial metals like titanium, stainless steel, and nickel alloys. By focusing this energy into an extremely fine spot, Fiber lasers achieve a relative density approaching 100%. This metallurgical integrity allows printed parts to reach mechanical performance levels comparable to forged components, far exceeding traditional casting.

Industrial Usage & Application Scenarios

- Aerospace: High-load structural parts and turbine components.

- Medical: Patient-specific orthopedic implants with complex porous structures.

- Electronics: Specialized heat sinks and conductive housings.

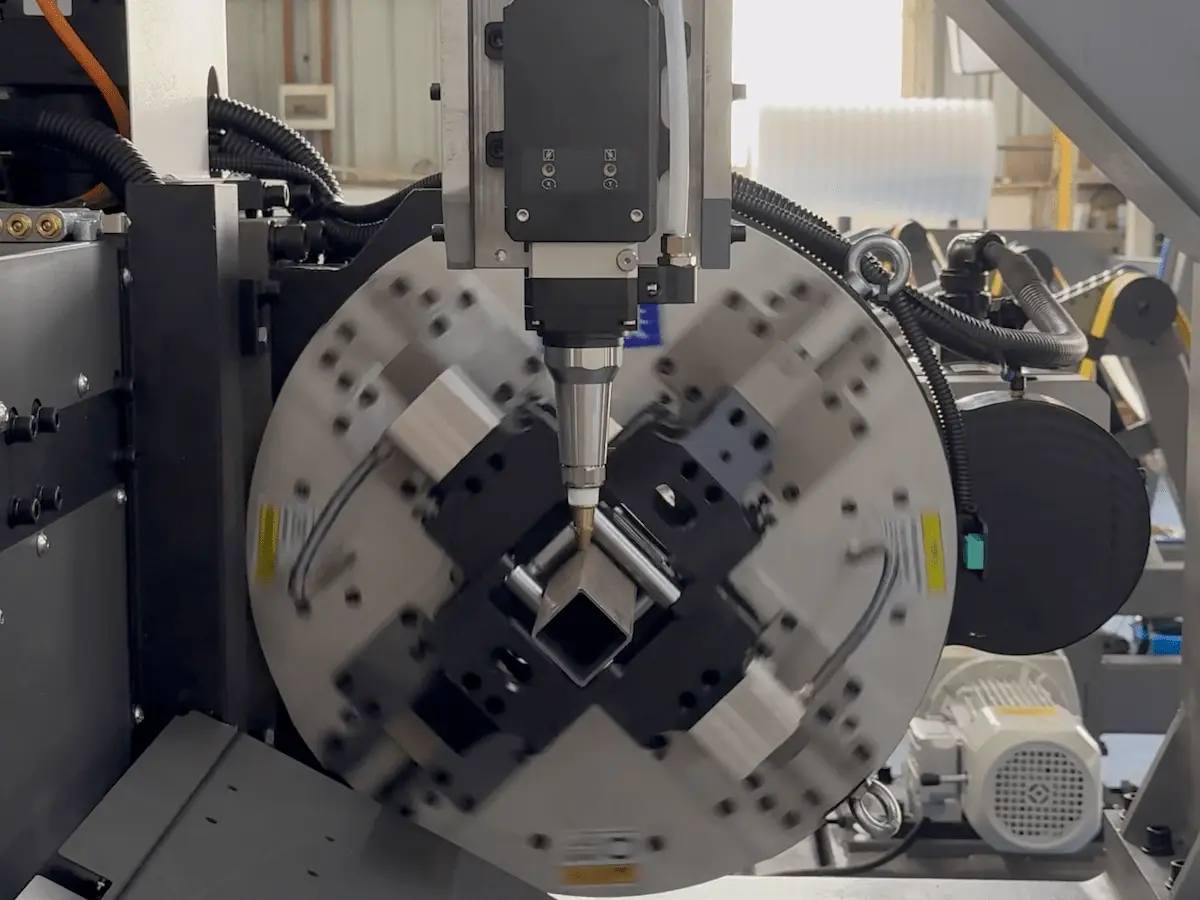

- Manufacturing: Beyond additive manufacturing, fiber lasers power high-precision fiber laser cutting machines for sheet metal fabrication and industrial component production.

Selective Laser Melting (SLM) is currently the most mature metal AM process. Its advantage lies in the “direct delivery” of functional parts. However, consultants must account for post-processing: parts are typically welded to the build plate and require Wire EDM or CNC milling for removal, adding to the total cost of ownership.

3. CO₂ Lasers: The Versatile Architect for Non-Metals

While Fiber lasers own the metal space, CO₂ lasers remain the foundation for non-metallic industrial processing, particularly within Selective Laser Sintering (SLS).

Generation Principle

The CO₂ laser is a gas-based system operating at 10.6 µm wavelength (with alternative wavelengths at 9.3 µm and 9.6 µm available for specific materials). The laser scans across a pre-heated powder bed. Rather than total melting, the laser provides the thermal energy necessary to “sinter” or molecularly bond polymers and ceramics under precise computer control.

The Key Differentiators: Competitive Landscape

The CO₂ laser facilitates a broader scope of functional materials, including nylon (PA12) and specialized polymers. Unlike metal-based systems, SLS utilizes the un-sintered powder bed as a natural support. This provides natural buoyancy and stabilization for the part during the build, enabling “support-free” geometries.

Industrial Usage & Application Scenarios

- Automotive: Ducting, manifolds, and high-durability functional interior components.

- Prototyping: Rapid iteration of complex geometric models without the need for support removal.

- Consumer Goods: High-strength, environmentally resistant final-use parts.

The lack of required support structures in CO₂ SLS processes significantly reduces labor costs in post-processing and allows for higher “nesting” density within the build chamber, maximizing throughput per cycle.

4. Ultraviolet (UV) Lasers: The Master of High-Resolution Polymerization

UV lasers are the strategic choice for applications where surface aesthetics and dimensional precision are the primary KPIs, serving as the energy source for Stereolithography (SLA).

Generation Principle

UV lasers utilize high-frequency ultraviolet light (typically 355 nm or 405 nm wavelengths) to trigger photopolymerization. As the laser scans the surface of a liquid photosensitive resin, it causes a localized chemical reaction that solidifies the liquid into a solid polymer layer-by-layer.

The “So What?” Layer: Precision vs. Strength

The short wavelength of UV light allows for a smaller focal point, making it the industry benchmark for resolution. While UV-cured resins typically lack the mechanical strength or heat resistance of metals or SLS polymers, they offer a surface finish that is often assembly-ready without aggressive sanding.

Strategic Comparison: SLA (UV) vs. SLM (Fiber)

| Funktion | SLA (UV Laser) | SLM (Fiber Laser) |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Quality | Superior / Smooth | Medium (Grainy) |

| Materialvielfalt | Limited (Photosensitive resins) | High (Various Metals/Alloys) |

| Part Size Capability | Small to Medium | Small to Large |

| Nachbearbeitung | Washing and UV Curing | Stress relief, EDM removal, Grinding |

| Mechanical Integrity | Brittle; low heat resistance | High; comparable to forged parts |

For dental models and high-precision injection molds, the UV laser’s ability to eliminate visible “layer lines” reduces secondary finishing costs, justifying the higher cost of resin consumables.

5. Nd:YAG Lasers: The Solid-State Foundation

The Nd:YAG (Neodymium-doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet) laser is a traditional solid-state pillar that continues to play a role in specialized direct metal forming.

Generation Principle

Nd:YAG lasers operate at a 1.064 µm wavelength (1064 nm). Although they share similar wavelengths with some Fiber lasers, the generation of the beam through a solid-state crystal provides a different stability profile and power delivery characteristic. The laser uses a neodymium-doped YAG crystal as the gain medium, pumped by flashlamps or diode lasers.

Evaluate the Impact

Historically, Nd:YAG was the primary heat source for early SLM systems. Today, while Fiber lasers have captured the majority of the AM market due to higher efficiency (fiber lasers achieve ~25% wall-plug efficiency vs. ~2% for lamp-pumped Nd:YAG), Nd:YAG remains relevant in Laser Cladding and heavy industrial repair applications where its specific absorption profile is preferred for building up material on existing large-scale components.

6. Diode & Pulsed IR Lasers: The Disruptor of Scaled Production

The emergence of “Area 3D Printing,” pioneered by companies like Seurat Technologies, represents a strategic pivot from single-point scanning to mass-scale production.

Generation Principle: The OALV Mechanism

This technology utilizes a modular pulsed infrared (IR) laser source combined with an Optically Addressable Light Valve (OALV). The system contains over 2.3 million individually addressable pixels. The process follows a specific four-step polarization sequence:

- Beam Shaping: The pulsed IR laser is shaped into a uniform square field (approximately 15×15 mm).

- Pattern Projection: A blue light projector overlays the part’s geometry (over 2.3 million pixels) onto the IR field.

- Polarization Control: The OALV changes the polarization of the IR beam: IR light overlapping with blue light pixels becomes horizontally polarized, while non-overlapping light becomes vertically polarized.

- Selective Melting: A polarizing mirror splits the beams, directing only the patterned (horizontally polarized) IR light to the powder bed to melt the entire area in one pulse.

The “So What?” Layer: Breaking the Cost Barrier

This “masking” approach allows for power levels 10-150x higher than a single laser system. Crucially, it decouples build rate from hardware cost. In traditional systems, doubling speed requires doubling the expensive laser heads; in Area Printing, speed is scaled by increasing the pulse frequency and energy density.

Scaling Roadmap & Milestones

NOTE: The following projections are company claims and should be viewed as targets rather than verified achievements:

- Current (Gen 1): Claimed manufacturing costs at lower rates than traditional AM.

- Future Generations: Company projections suggest significant cost reductions and speed improvements in coming years.

Unlike SLM, Area Printing introduces new constraints: pulse energy control, pattern size limitations, and a fixed layer thickness of 25 µm.

7. Conclusion: Choosing the Right Laser for the Future

The five types of lasers—Fiber, CO₂, UV, Nd:YAG, and Diode/Pulsed IR—constitute a complete toolkit for modern manufacturing. Strategic selection should be guided by key Selection Principles:

- Usage Requirements: Determine if the end-goal is a non-functional prototype (SLA/UV) or a high-load final component (SLM/Fiber).

- Material Quality: Assess the required relative density. Metals require Fiber or Nd:YAG; polymers utilize CO₂.

- Procurement & External Environment: Consider the total cost of ownership, including the specialized labor required for SLM vs. the simplified workflow of SLS.

- Post-Processing Costs: Factor in the “hidden” costs of support removal, thermal stress relief, and surface grinding, which can often exceed the cost of the print itself.

As the industry moves toward 2030, the shift to Area Printing and other emerging technologies suggests a future where additive manufacturing is no longer a niche prototyping tool, but potentially a primary mass-production technology.

For further technical standards on additive manufacturing processes, refer to the ISO/ASTM 52900 Standards.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

1. What is the most widely used laser type in metal additive manufacturing?

Faserlaser are currently the most widely used and mature laser technology for metal additive manufacturing, particularly in Laser Powder Bed Fusion for Metals (PBF-LB/M) systems.

They offer high energy efficiency, excellent beam quality, and stable melting behavior, enabling metal parts to achieve relative densities above 99.5% under optimized conditions.

2. Why are fiber lasers preferred over CO₂ lasers for metal 3D printing?

Fiber lasers operate at a wavelength (~1.07–1.09 μm) that is well absorbed by most industrial metals, such as steel, titanium, aluminum, and nickel alloys.

In contrast, CO₂ lasers (10.6 μm) are poorly absorbed by metals but highly effective for polymers, making them unsuitable for metal powder bed fusion.

3. Are CO₂ lasers still relevant in industrial additive manufacturing?

Yes. CO₂ lasers remain the industry standard for polymer powder bed fusion (PBF-LB/P).

They are widely used to process materials such as PA12 and PA11, offering support-free printing, high batch productivity, and stable performance for functional polymer parts.

4. What is the main advantage of CO₂-based SLS compared to metal PBF systems?

The key advantage is that no support structures are required.

Un-sintered powder naturally supports the part during printing, which reduces post-processing labor, lowers production costs, and allows higher nesting density within the build chamber.

5. Why do SLA systems use UV lasers instead of fiber or CO₂ lasers?

SLA and other vat photopolymerization processes rely on photopolymerization, which requires ultraviolet (UV) light to cure liquid resin.

UV lasers offer short wavelengths and small focal spots, enabling exceptional surface finish and dimensional accuracy that cannot be achieved with infrared lasers.

7. What is the difference between fiber lasers and Nd:YAG lasers in metal AM?

Both fiber and Nd:YAG lasers operate near a 1 μm wavelength and can process metals effectively.

However, fiber lasers offer higher efficiency, better beam quality, and lower maintenance, which is why they have largely replaced Nd:YAG lasers in modern metal powder bed fusion systems.

Nd:YAG lasers are now mainly used in directed energy deposition (DED) and repair applications.